In 2045, Shopping at the Center for Mind Design

/I’m pretty sure I think more about brain enhancement than most people. It has occurred to me that this may be because my brain simply is in greater need of enhancement than others. At any rate, I am constantly inventing strategies to improve my neural functioning, both by correcting what I perceive as faults in my cognitive operation and imagining new features that the neural auxiliary of my dreams would offer.

Instant replay is high on my list, enabling me to easily retrace the route I must follow to find my keys.

Photographic memory is another. I would very much like the ability to create exact images — or even short moving pictures with sound — of any scene in my life, an app that’s able to probe and exhume the memories stored as proteins in the deep recesses of my hippocampus.

More simply, I’d be pleased just to create a simple shelf in my conscious awareness where I can stow priority items that I, at all costs, must not forget. But here’s the problem: the mental shelf I imagine installing for this purpose keeps disappearing along the items I place on it.

In the introduction of her book, Artificial You: AI and the Future of Your Mind, Susan Schneider invites us to participate in a more elaborate mental exercise. Imagine the year is 2045. We’re on a shopping trip and our first stop is the Center for Mind Design.

She writes:

“As you walk in, a large menu stands before you. It lists brain enhancements with funky names. Hive Mind is a brain chip allowing you to experience the innermost thoughts of your loved ones. Zen Garden is a microchip for Zen master level meditation states. Human Calculator gives you savant level mathematical abilities….You can order a single enhancement or a bundle of several.”

Her point:

“Our brains evolved for specific environments and are greatly constrained by anatomy and evolution. But AI has opened up a vast design space, offering new materials and modes of operation, as well as novel ways to explore the space at a rate much faster than biological evolution. I call this exciting new enterprise Mind design. Mind design is a form of intelligent design, but we humans, not God.”

Mood Regulation

In Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, the novel he wrote in 1968 that inspired the making of Blade Runner in 1982, Philip K. Dick engaged in a bit of mind design, offering us the Penfield Mood Organ as a bedside neural auxiliary that allowed users to dial in their desired emotions and states of mind.

Dial 888, for example, and you would experience a desire to watch TV, “no matter what was on.” Dial 481 to experience “an awareness of the manifold possibilities” open to you in the future. Dial 594 to experience “pleased acknowledgement of husband’s superior wisdom in all matters.”

Dick named the device for Wilder Penfield, an acclaimed neuroscientist who achieved remarkable results with electric brain stimulation, working with patients suffering epilepsy and exploring the foundations of memory and hallucinations.

It has always seemed to me that mood is a thing we should be better equipped to manage. To some extent, it’s an ability we already possess.

For example, the mere act of smiling for no reason will brighten whatever mood we might be experiencing. Our brains perceive the muscle activity that goes into a smile as a sign that we’re happy. Smiling activates the release of dopamine, endorphins and serotonin, all of which are associated with happiness and stress relief. Smiling also mitigates the action of cortisol, a stress-induced hormone.

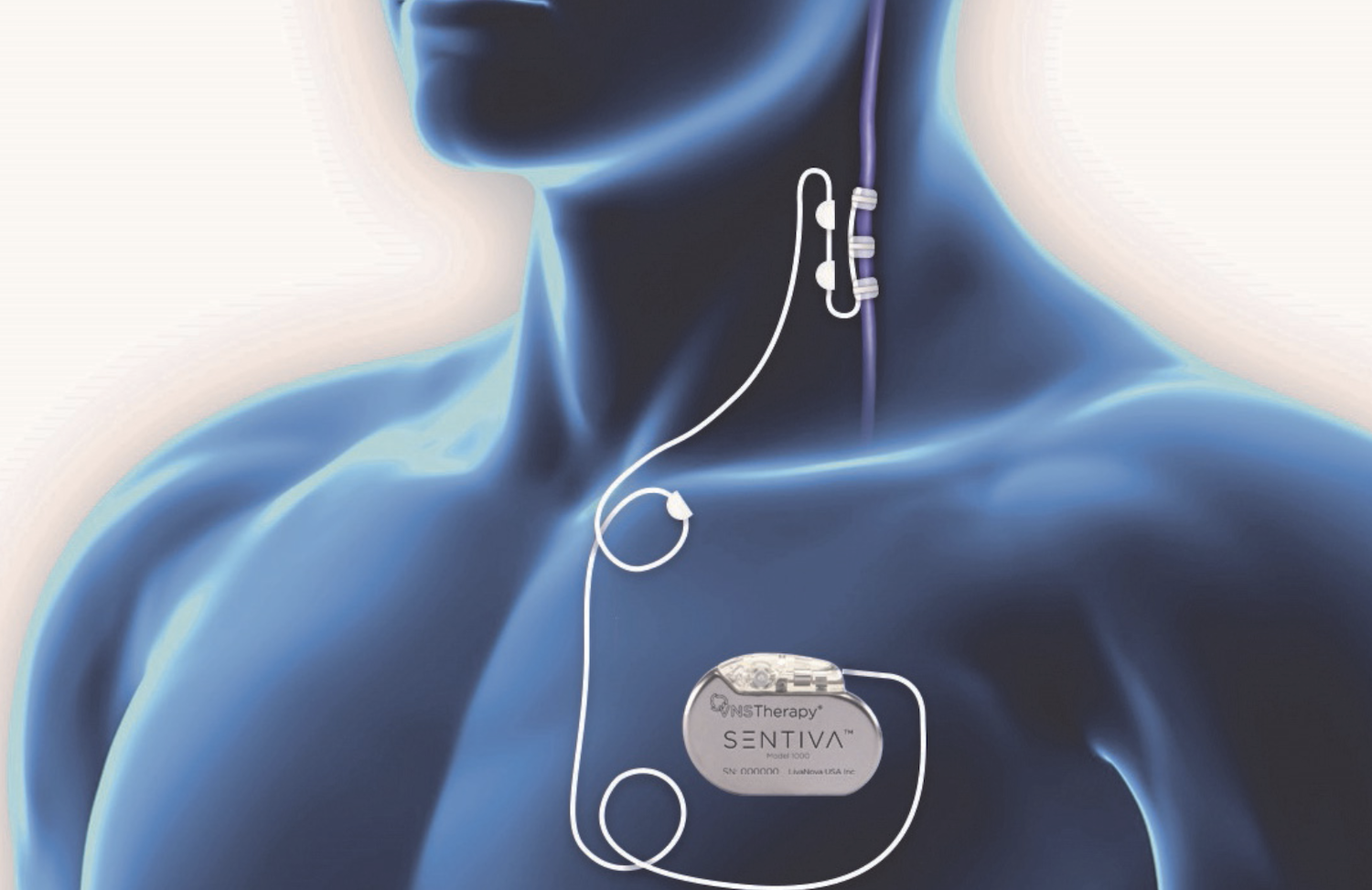

We also can brighten moods by electrically stimulating the vagus nerve. Since 2005, therapists have been using pacemaker-like devices the size of stopwatches to help patients with treatment-resistant depression. They place them in the upper chests of patients and attach them to the vagus nerve, which wanders downward from the brain’s medulla oblongata — which drives our hearts, lungs, and stomach — to the abdomen.

Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS) promotes the action of the same neurotransmitters that antidepressant medications address, including serotonin, norepinephrine. Promoting neuroplasticity, it also reverses changes in such areas as the hippocampus and prefront cortex that produce chronic depression.

It’s not the Penfield Mood Organ — but it’s a start.